Are we not trees?

What do we, as humans, have in common with the ancients?

Standing tall with knuckles burled, we seek the caress of a willing sun. We yearn for the touch of hope on our receding hairlines. For the flush of warmth to our bark. In a long moment of stretch, we branch out with our gnarled fists aiming skywards.

In this action, huddling strong in grove and dell and chaparral, are we not the final stand?

We are a defiant swatch of color painted on an indifferent world, and like the trees, we do not give in.

Knowing the inevitable, we add to our rings. Year-after-year-after-year, we live while accumulating the record of our dying. We absorb our imperfections, growing knots of knowledge while adding to our timelines.

This is where we were hurt, and this was what hurt us. A fire, a flood, an especially harsh winter for love.

In our resilience—our defiance of the parameters we exist within—we are as the Joshua, the Redwood, and the Oak. We continue our existence. We carry on with our carry-on.

We are the trees of our potential for magnificence, growing wild.

Seeking a quiet I cannot find, and feeling I have forgotten, I race for the trees, for the mountains, for the sky. It’s a spur-of-the-moment thing, this trip. Spontaneous. Unexpected. Needed.

I seek. I am seeking.

Seeking connection with the real of, the true thing, the back-and-forth conversation between soul and nature.

I will look for it in the trees.

Loading up my motorcycle with minimal gear—I will eat on the road, I will stay in hotels, and like a leaf in the wind, I shall go where I am taken—I head out early on a Thursday morning. Toward Mount Hamilton and the Lick Observatory. Toward the trees of the Sierras.

With a rough route mapped and loaded on my GPS, I ride. Hair flapping and neck exposed to the chill of the morning, I stop once to check the security of my tie downs, then again at the base of Mt. Hamilton to change gloves before beginning the first taste of the twisties on my way up to Lick.

I have missed this. The loose objective with no real plan beyond getting from A to B. What happens along the way—the alphabet of possibility—is up for grabs. Vista points and roadside diners. All are in play.

Tonight, I will stay in Jamestown. Tomorrow I will throttle my way up and over two mountain passes–Sonora and Monitor. Eventually, I will work way back through Yosemite. Four days, I estimate. Back in time for work on Monday, with my mini adventure done and my soul saved by trees.

Over Hamilton I go, and after a quick stop at the Observatory, I head down the backside of the mountain and into an oven of sorts. The Central Valley. There’s a heatwave coming, they say, but I should be done early in the afternoon. There'll be plenty of time to cool down, especially if the hotel has a pool.

It feels good to be out in the world. Out at the edge of trees. The low-lying California Oaks open their arms to me in the foothills as I noodle my way through the heat and traffic, miles disappearing behind me.

Arriving at a cheap and stiff-sheeted hotel room in Jamestown, defeated by the afternoon heat and with a tired clutch hand, I kick back and eat Fritos for dinner on a hotel bed as the sun goes down.

“I should go look for the pool,” I think, but decide not to. I’m too settled now with shorts on and aircon flowing. The Nacho Cheese Fritos are good, and the NA beer is hitting the spot.

This is LIVING!

On the morning of July 4th—the next day—after a failed attempt to find a diner for breakfast in both Sonora and Jamestown, I begin my ascent to the top of Sonora Pass. It’s early, so I have the road to myself as I twist the throttle of my small motorcycle and glide and carve and decompress my way up to the top of the pass.

Past creek-side campsites. Past granite outcrops. Past snow melts and pullouts with spectacular views.

Through an audience of bark and needle and cone, I lean and twist and make my way up as random chipmunks and squirrels dart across the road. I cringe and brace for the bump, every time.

“Commit, you idiots! Don’t change direction right in front of my wheel.”

They survive. Everyone—and thing—survives.

And me?

I am simply a plug seeking an outlet. I am winding my cable through the world.

The miles tick by through pines and aspens and meadows. The connection is once again made, and the recharge is on.

Sonora Pass

With our potential to rot at the root, are we not a reflection of the potent creep of bad soils and tainted waters? With poisoned cores, our barks stripped away and our trunks naked, we are slowly consumed by blind and hateful termites.

In this new horror state, we observe our glorious old growths stunted by hot temperatures and fluctuations in the atmosphere. We are overwhelmed by our precarious views.

When treated with care, we come back from the brink of this mighty crack-and-fall fate, but when left in the dark of our hothouse, we shrivel to curdled branch and desiccated leaf.

We are the widow makers. The roof takers. The road blockers, all.

There exists within us an evil and malevolent sap—a threat to our delicate structures. Surging through the trunk, the branch, the root, the stem, it leaves us vulnerable to falling hard, without warning, and taking down everything within reach of our shadow.

But we are not dead yet!

We are the trees of our downfall, disease detected, and searching for the cure.

Day three opens with breakfast in the lobby of a quaint inn in Woodford, and after consuming a croissant (which I will generously describe as ‘passable’), I head back to Monitor Pass again to go visit an old friend.

A Juniper Tree.

Making the turn onto the pass, I begin the ascent. The pavement is smooth and—again—traffic-free. It is a cool morning, but the sun is warm and strong as I climb up through the valley and toward this tree. I’d ridden past it yesterday (in the opposite direction) and glanced up to check if it was still standing. A fire had ripped through this area a few years prior, and many trees had not survived.

“What is the fate of my proud Juniper, holding court up above a sweeping curve?” I was stoked to see that it was still there as I'd zoomed past.

Today, it was time to pay a proper visit.

In a gravelly pullout just beneath the tree, I kick out the stand of my motorcycle, take off my helmet, and admire the view of the valley below. There is not a cloud in the sky.

Turning toward the tree, I scan for an easy scramble point up to it before clomping through the rocky outcrop and toward my old pal. Ticks. I think briefly of ticks and make a mental note to check my laces when I get back to the bike.

“Hello,” I say, arriving at its base. (Yes, I talk to trees. I will not pretend that I don’t.) “You haven’t changed a bit.”

This may or may not be true, and I don’t have the time nor the signal to check on photos I took over ten years ago of this exact tree.

It's time to update the record.

[snap] [snap] [snap]

I take new photos of my friend. Frame it against the sky. Do the standard selfie with me in front making different faces, while it maintains its stoic expression behind me.

There is no signal here, and yet, I feel the most connected I’ve felt in a long time. With myself mostly. It’s quiet. There have no distractions for me here.

Turning away, I look out at the view in front of me–at what my friend the tree looks at every day—and absorb the scene.

"It’s just a tree, Janeen. It’s not magic."

Yeah, I guess you're right.

Even so, here we are. Together, we sit in quiet and easy company. We watch as a cyclist passes by on the road below us.

We wave our branches, but he doesn’t look up.

People, you’ve got to look up! You’re missing everything!

Visiting with an old friend on Monitor Pass

With our crowns tilted, we brace ourselves against the howling winds of the world. Imperfect and dented beings, we lean into our fate, choosing to press on against the tyranny of a wicked gale, a brutal storm, a derecho not of our making.

Are we not like trees? Do we not fight daily to prove our love of this life? To protect our precious kingdoms with the rugged bark of our backs and the reach of our strongest branches?

Our limbs crack under the strain of our lifelines, stretching out and over the world to explore new frontiers. To set down roots of their own. To grow. Our cones, our pods, our fruits. We drop our dreams in impossible times, seeking damp spaces, rocky faces, and sun-lit places.

No kings, they say. No queens either.

Ours are not the crowns of monarchs. They are the bite of our teeth upon the crust of this earth.

We are the trees of our un-sprouted future, bursting defiant, persisting in our resistance.

I stay a few days in Bishop because I didn’t plan at all. Relying on bad intel, I’d failed to realize in time that while you don’t need a reservation to ride through Yosemite anymore, you DO need one between mid-June and mid-August. I still managed to get one for a three-day window of opportunity, and while I could’ve squeezed all the way from Bishop to home on Sunday late, I wanted to be safe and relaxed with my riding. No rush. Bishop, then Lee Vining, then home.

But first, today.

On a hot afternoon in Bishop, hunkering down at a hotel that seemed to have cemented over the pool to create an outdoor area no one could sit in in this heat, I lay on the bed and cast my cursor around on Google Maps for somewhere to ride my motorcycle the following day.

And then I saw it—the opportunity to visit with some old folks at the Ancient Bristlecone Forest.

Backstory. Before I ever moved to these United States, back in 2003, I read a story about the fate of Prometheus, possibly the most famous Bristlecone Pine, and had longed to see Bristlecones in person ever since. The story of Prometheus is well known.

In 1964, a student from UNC, Donald Currey, hiked up Wheeler Peak in Nevada. In a pursuit of knowledge—he was studying tree rings as part of researching the climate of the Little Ice Age—he'd decided to do some ring-reading of some Bristlecone Pines. Hence the hike.

He picked a random tree for his study, which he logged as WPN-114, and proceeded to drill his little core sampling tool into the ancient being. Now the story gets a little fuzzy. I’ve read conflicting reports as to the specifics, but either the tool broke off in the tree, or he was having trouble getting a good sample…. Either way, that doesn’t really matter. It was a problem that needed solving, so he approached the U.S. Forest Service, explained his tool was caca, and their solution was to, wait for it, cut the tree down.

As horrible as that sounds, the part of the story that triggered—and horrified—me was not so much the cutting down (yes, a tragedy) but more the recognition within myself of the stomach-dropping feeling that young Currey must’ve had when he began to count the rings on the WPN-114 cross-section.

It's that sinking feeling—the burn of it—that occurs in the moment when you instantly realize you’ve made a colossal, catastrophic, and what will probably be an unforgivable mistake.

4,844 rings.

Yes, by cutting it down, they had just killed the oldest recorded living organism on earth at that time. Later they adjusted the age to around 4,900, give or take. Details! (Add a few more years to that lump in your throat, Donald.) I don’t know when it was dubbed Prometheus—before or after—but what a story!

The current oldest organism at 4,853 years old is another Bristlecone Pine in California named Methuselah, although they say there are undoubtedly older ones out there. Methuselah’s exact location is kept secret, but that brings us neatly back to today.

Today, the hike around the Methuselah Loop in the Bristlecone Pine Forest was on my docket.

With a real croissant from a bakery in my belly, I set off.

The ride up to Schulman Grove and the Bristlecones can only be described as a dream motorcycle ride, and what is probably a BRUTAL bicycle ride. One that I will absolutely come back and check off my list one day. It is narrow and twisty and steep in places, and the views of the snowcapped Sierras are incredible this time of year.

In the parking lot, I change into my Danner boots for the four-mile loop (I’ve learned the hard way not to try hike in my moto boots), duck into the visitor center to check in and get some recommendations, then set out for my one-on-one audience with the world’s oldest trees.

Each step is a ‘Wow!’ and ‘oooh’ and ‘ahhh’ moment. There are no crowds, so I don’t hold back with expressing my appreciation out loud. The day is hot and forecast to only get hotter, but the breeze at elevation is delightful and takes the edge off it.

Here’s a quick summary of Janeen interacting with the bristlecones. I take too many photos of them (it killed my phone at mile 3) and I talk the to myself and the trees for the whole loop. I give compliments to any lump of wood that’s putting on a show and catches my eye. After a mile or so, I feel an elevation headache coming on and proceed to drink all my water. I sit on a bench and eat a sandwich, gazing out at a view of even more Bristlecones on the hill opposite.

The wisdom of trees overwhelms me.

Tell me your secrets!

Nothing.

It’s fine. Be like that. I swing my legs under the bench. I listen. Nothing but the wind and the birds and the sound of my heaving breath settling down after the shock of hiking at altitude.

Shhhh!

The ancients are speaking. I listen; my ear tuned to the wind.

“Silence is not some hole to be filled,” they say. “Leave space for growth.”

Put that on a card. That’s fridge-door gold.

We can give our all, just like trees. We can shade against the brutal heat and provide shelter in a storm. We can give our bodies to the cause, creating joyous habitats as we do so. Real ecosystems of yes and can.

Our heartwoods can be rich and deep and filled with welcome refugees. Of memory. Of circumstance. Of love and grief and triumph.

Within the forest of our footprint can exist the wildest of lives, beginning.

We can be the trees of benevolence, photosynthesizing empathy with every ragged breath.

Early on Wednesday morning, I fire up the bike and swing by the gas station at the bottom of Tioga Pass to fill up, with a goal of reaching the entrance to Yosemite by 7 a.m. (ish). The air is cold as I climb, and each time I dip into shade, despite the winter gloves and hoodie under my riding jacket, I shiver.

It’s cold. I know it’s going to get colder the higher I go. Leaving just after sunrise has its drawbacks, but I don’t mind. It’ll warm up eventually, as will I.

The previous night, I’d researched the best time to get to the gate and avoid lines, and in the end, it was a pointless worry. I rolled up to the ranger’s little hut and said hi. There were ZERO people in the line.

“I guess I picked a good time to come,” I said.

“Oh, this is the perfect time. You nailed it!”

Nailed it! A travel victory. One must always celebrate a travel victory, no matter how small. In this moment, I decide I have no regrets about being so early.

For the next hour or so, I decide I have regrets about being so early. My hands are freezing. But that’s my only regret. Yosemite just after sunrise is stunning. I stop at a meadow to take a photo and make the mistake of taking off a glove. My right hand protests and I quickly shove the glove back on, but it’s too late. The cold is too rude, and this bike has no faring, so I just take it. Whatever. I power on, rejoicing in the brief interludes sunshine when I can.

Celebrate the small victories.

Winding through the avenues of trees and past early-morning hikers heaving their day-hike packs on, I pull over to the vista point that looks straight down the valley at Half Dome. The parking lot is empty, which is a first for me at that view. I park my bike sideways in a space and take more pictures of pictures I have taken many times before. I just can’t help myself.

It’s been too long, Yosemite. Too long.

Still on Tioga and well inside the park, I stop at a pullout just before Tenaya Lake, take off my glove again, and flip up the visor of my helmet. Mosquitos are instantly on me, buzzing around my face and all over my hand—the only two pieces of skin on offer. Needless to say, it is the quickest of gear checks and photo ops.

If the trees are laughing at me, they don't let on.

I have driven through this park a few times; have ridden my bicycle through the Valley in the fall (it’s a glorious loop); and driven up and over and through, but never via the 120 and out to Groveland.

To mix things up this trip I decide to go that way when I get to the turn. It feels weird though, to skip the best bits, and while the 120 has some nice features, it's not as mind-blowing. It would’ve been nice to see El Capitan. Oh, well. Next time.

I exit the park and through the foothills, then head back out and into the Central Valley to retrace my path from a few days earlier to come back over Mount Hamilton. Five hours, give or take.

Back in the familiar Redwood trees, I wind my final descent down San Jose Soquel Road to home, butt dead, and hands throbbing.

The tree-seeking 7-day loop closes and the circuit. The circuit is complete.

I am rewired. I am reset. Through the roots and the branches and the bark and the trees, the connection is restored.

Are we not trees?

Look at us, with our stubborn minds and resilient attitudes. Us, with our verdant loves and swaying bodies. Look.

Despite our could-be-rotten timbers and might-be-decaying minds, look at how we seek to make impossible connections and build and grow and flourish. Seeking to put down roots in a place where we can just be. Look at how we cling to each other to breathe life into our worlds.

Are we not trees?

Deep within the sap of our bodies lies the memory of the ancients. Look at what can be made of us, and of what we can make of ourselves.

Are we not trees?

Look how easily we are cut down, felled by injustice, and blown over by the madness of environmental forces well beyond our control.

Are we not trees?

We grow fast and burn quickly. We land hard, crashing through power lines and crushing backyard fences with helpless regularity, blacking out entire zip codes as we fall.

Look.

In the roughed-up bark of our armor and the fragility of our existence, I ask you.

How are we not?

BONUS: Walk the Methuselah Loop with me (well, the highlights). It's eleven minutes of me showing trees and yaking away and being, generally, obsessed.

This week’s amends…

PROMETHEUS

By Lord Byron

Titan! to whose immortal eyes

The sufferings of mortality,

Seen in their sad reality,

Were not as things that gods despise;

What was thy pity's recompense?

A silent suffering, and intense;

The rock, the vulture, and the chain,

All that the proud can feel of pain,

The agony they do not show,

The suffocating sense of woe,

Which speaks but in its loneliness,

And then is jealous lest the sky

Should have a listener, nor will sigh

Until its voice is echoless.

Titan! to thee the strife was given

Between the suffering and the will,

Which torture where they cannot kill;

And the inexorable Heaven,

And the deaf tyranny of Fate,

The ruling principle of Hate,

Which for its pleasure doth create

The things it may annihilate,

Refus'd thee even the boon to die:

The wretched gift Eternity

Was thine—and thou hast borne it well.

All that the Thunderer wrung from thee

Was but the menace which flung back

On him the torments of thy rack;

The fate thou didst so well foresee,

But would not to appease him tell;

And in thy Silence was his Sentence,

And in his Soul a vain repentance,

And evil dread so ill dissembled,

That in his hand the lightnings trembled.

Thy Godlike crime was to be kind,

To render with thy precepts less

The sum of human wretchedness,

And strengthen Man with his own mind;

But baffled as thou wert from high,

Still in thy patient energy,

In the endurance, and repulse

Of thine impenetrable Spirit,

Which Earth and Heaven could not convulse,

A mighty lesson we inherit:

Thou art a symbol and a sign

To Mortals of their fate and force;

Like thee, Man is in part divine,

A troubled stream from a pure source;

And Man in portions can foresee

His own funereal destiny;

His wretchedness, and his resistance,

And his sad unallied existence:

To which his Spirit may oppose

Itself—and equal to all woes,

And a firm will, and a deep sense,

Which even in torture can descry

Its own concenter'd recompense,

Triumphant where it dares defy,

And making Death a Victory.

I couldn't make up my mind as to which tree song I'd add here, and my first thought was Belly. But then I had a flashback to some CLASSIC Aussie 80s rock from the iconic lads, Cold Chisel. Absolute master class in songs as stories with this one. BONUS!

On Rotation: “Flame Trees” by Cold Chisel.

On Rotation: “Feed the Tree” by Belly.

A reminder that all songs featured in this newsletter over the years are added to the giant mega super playlist of magnificence which you can access with an effortless depress of this button. 👇

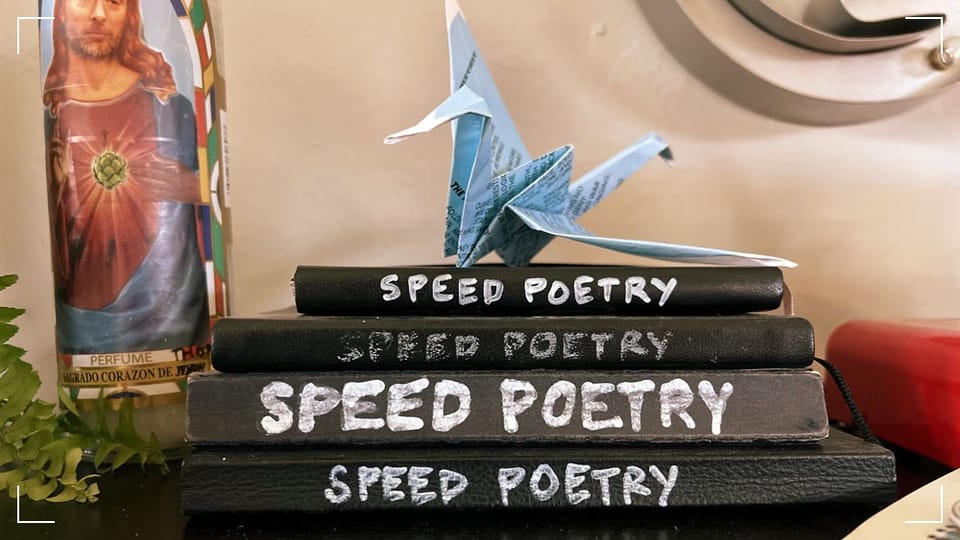

The only thing in this week's post that is not tree related. 100% would eat. (But I don't think that's the goal).

Some trees I have visited with in the past, some MANY times (including The Mother Tree, image 1.) Sequoias, Ponderosas, California Oaks, Redwoods, Joshua Trees. I'm not even going to open the can of worms (not woodworms) that are the Aussie trees I have known.

Shameless Podcast Plug

Listen to audio versions of early issues of The Stream on my podcast, Field of Streams, available on 👉 all major podcasting platforms 👈

Here’s Apple